There’s been a lot of press lately about all the plastic crap in our oceans. For example, this Mother Jones article of a week ago has metastasized and been re-posted many times. In the article, there are some (seemingly) alarming claims, such as:

- There are up to 28 billion pounds (12.7 million metric tons) of plastic in the oceans;

- There’s an accumulation of junk (the great Pacific garbage patch) which is twice the area of Texas.

Now, I will be the first person to condemn pollution, promote biodegradability, and sing the praises of sustainability. However, these numbers (if taken at face value, and I have no reason not to) don’t necessarily make a very strong case that the oceans are filled with junk.

The problem is that the oceans are just so ridiculously huge to begin with.

Let’s do some simple math. All of the oceans on the planet have a combined volume of about 1.3 billion km3, which is 1.3 x 1018 m3. At roughly 1000 kg/m3, this has a total mass of 1.3 x 1021 kg, which corresponds to a weight of 2.87 x 1021 pounds. So we get the following ratio:

28 billion pounds ÷2.87 x 1021 pounds = 9.8 x 10-12.

That’s a pretty small fraction. To put it into perspective, let’s say the world’s oceans were an Olympic sized swimming pool, with volume of 2500 m3 and a mass of 2.5 x 106 kg. On this scale, all of the plastic in all the world’s oceans would have a mass of (2.5 x 106 kg) x (9.8 x 10-12) = 24.5 mg, which is about the mass of a housefly.

Let me stress: all the plastic we’ve dumped in all the oceans is about like a housefly tossed into an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

But what about that Texas thing? A pile of junk, twice the size of Texas, just floating around? That has to be bad, right?

The area of the world’s oceans is ~3.6 x 108 km2. Twice the size of Texas is 2 x 696,241 = 1.39 x 106 km2.

This gives a ratio of 1.39 x 106 km2/3.6 x 108 km2 = 0.0039 = 0.39%. That’s small, but a much bigger fraction that before. Not surprisingly, our plastic junk takes up a higher fraction of the oceans’ area than it does the mass, because the junk floats on the surface.

Returning to the Olympic sized swimming pool: its area is 50 m x 25 m = 1250 m2. Since 0.39% of that should be floating junk, we get 1250 m2 x 0.39% = 4.875 m2. That’s a floating trash pile 2.2 m x 2.2 m on a side, bigger than the area of a swimmer…it’s about the area of two pool floats. That’s big enough to notice. That’s big enough to worry about.

To summarize: the great Pacific garbage patch is like two pool floats in an Olympic sized swimming pool. But these are thin floats: remember, they can’t weigh more than a housefly!

This analysis is optimistic and pessimistic in equal measures. On the one hand, in terms of mass, the amount of plastic we’ve chucked into the ocean is a pittance, in part because the oceans are so deep. On the other hand, since plastic floats, it takes up a disproportionate amount of the oceans’ surface area (a place where most marine life lives anyway). Even if it’s less than 1% of the area of the whole pool, a couple of pool floats is certainly a distraction if Olympic swimmers are trying to have a race. My suggestion is that we should strive to…

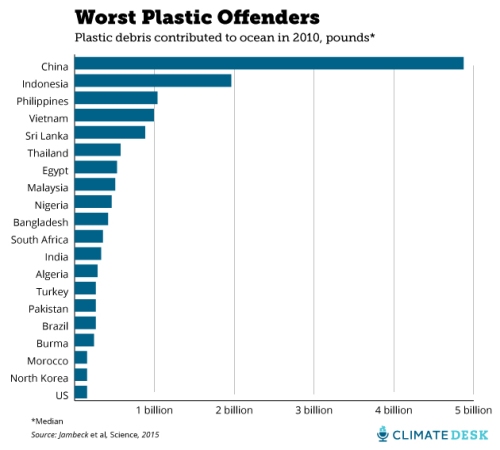

Oh, who am I kidding. Look at this graph (again, from that Mother Jones article):

If China doesn’t change its ways, it doesn’t matter what we do.